Date published: 16/08/18

Bacteria and binding polymers

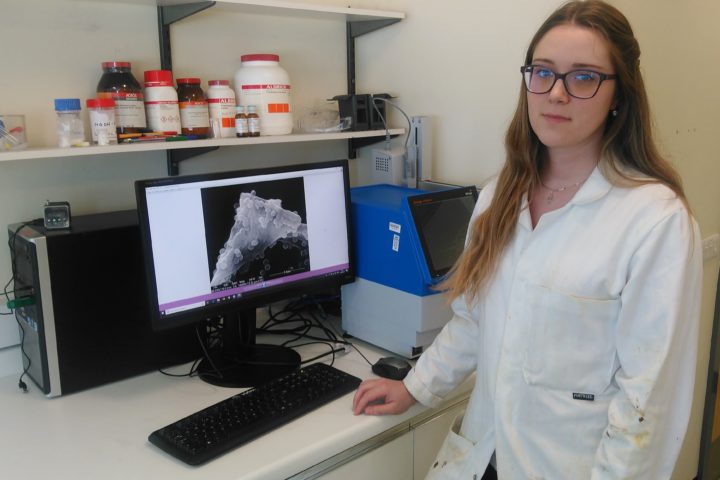

- Name: Mariya Kalinichenko

- Current Organisation: University of Bradford

In May, Translate opened its summer student project scheme to support small medical technology development projects in the Leeds City Region. The scheme proved to be a massive success and 26 unique projects were funded. Learn more about their work in this blog.

This summer I had the wonderful opportunity of working in a placement program that allowed me to learn a range of new scientific techniques and develop some skills. I joined Dr Swift’s group to work on Polymer/Bacteria sensing technologies, primarily to analyse and characterise the polymer/bacteria combinations.

After starting work I spent several days working with Dr Katsikogianni’s group preparing three different strains of bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa). We cultured these bacteria in her laboratory and prepared various mixtures / combinations of Dr Swift’s sensing polymer / bacteria in solution.

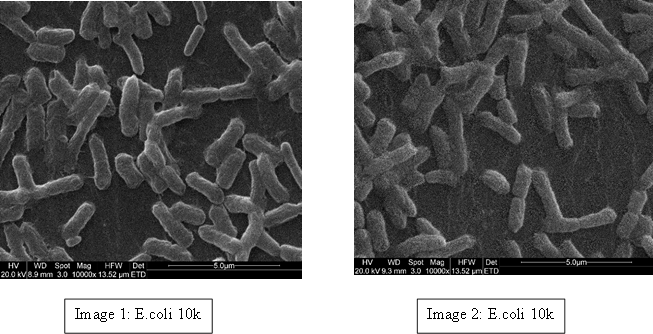

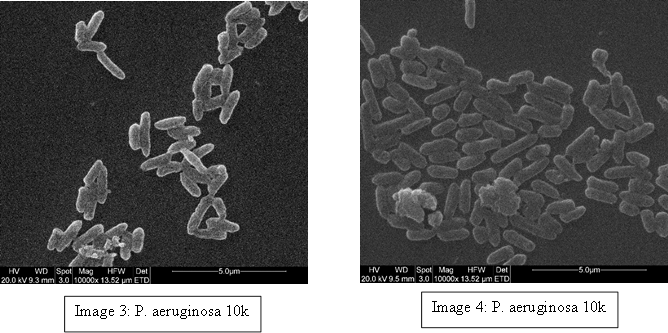

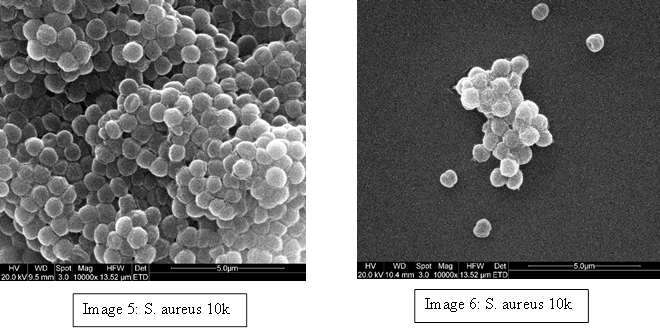

The main instrument I have used to look at the bacteria is Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). I had not had this opportunity before and enjoyed being trained to operate the microscope. After several training sessions I was given permission to work autonomously.

Using this instrument is very different from the chemical experiments I have been doing over the last two years, and I have learnt a lot by examining samples with bacteria both alone and with Dr Swift’s binding polymer solution.

To demonstrate we have examples of these bacteria below; E. coli (Image 1 & 2), S. aureus (Image 3 & 4) and P. aeruginosa (Image 5 & 6). Even though most E. coli strains are harmless and S. aureus is a member of the normal flora of the body, frequently found in the nose, respiratory tract, and on the skin, they can be dangerous. For example; some E. coli serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, S. aureus is a common cause of skin infections including abscesses, respiratory infections such as sinusitis, and food poisoning and P. aeruginosa is associated with serious illnesses – hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia and various sepsis syndromes.

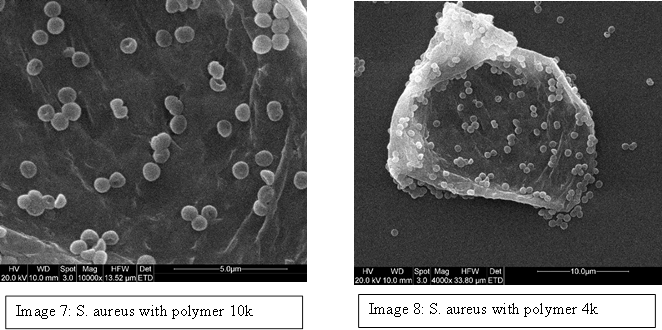

We prepared free bacteria samples, and combined them with the branching polymer designed to target S. aureus and the results were incredible. It was observed that the polymer actually interacts with the bacteria, making it aggregate to the polymer (Image 7 & 8). We tried many different variants of the polymer, testing the different concentrations that would encourage the material, and eventually found a ratio where there was no free bacteria in solution but all of it was bound to the polymer material.

This summer program also allowed me to learn many other techniques used to analyse polymers including size exclusion chromatography (SEC), NanoDSC, UV-vis and Fluorescence. With the remaining time left this summer I have attached a dye to the polymer backbone and currently testing how its fluorescence responds to the presence of bacteria. In summary this project has taught me lots about scientific research, developing quality management skills and trained my method development expertise.

You can find more about Dr Swift (and collaborators) research at www.polymerbiomateirals.com, and the polymers I am studying were recently reported by Teratanatorn et al, Biomacromolecules, 2017, p2887-2899.